ATHABASCA — The house hippo was part of a Canadian media campaign 20 years ago that aimed to teach Canadians you can't always believe what you see, and now a similar campaign for the COVID age is encouraging Canadians to ‘Break the Fake’.

In a recent presentation to the Rotary Club of Athabasca, Media Smarts director of research Kara Brisson-Boivin, gave Rotarians several strategies to verify news sources including the use of fact checkers; finding original sources of stories; using tools like Google or Wikipedia to see if a source is real; and comparing news outlets to see if the same or a similar article can be found.

“There isn’t an easy way to spot misinformation online, certainly not by looking at images or news,” she said. “And that’s because it is so easy to make a fake website; it is as easy to make a fake website as it is to make a real one.”

Media Smarts teaches people about online issues including digital parenting, privacy, hate, misinformation, activism, algorithms, and artificial intelligence.

“Sometimes people share misinformation by accident because they really think something is true and it's not or because they don't think other people will take it seriously,” said Brisson-Boivin. “And most of us have probably shared something we thought was real without checking and we're more likely to share things that we feel strongly about, especially things that we hope are true.”

The original house hippo campaign was about truth versus fiction and has been revived to remind people they need to fact-check before hitting the share button on social media.

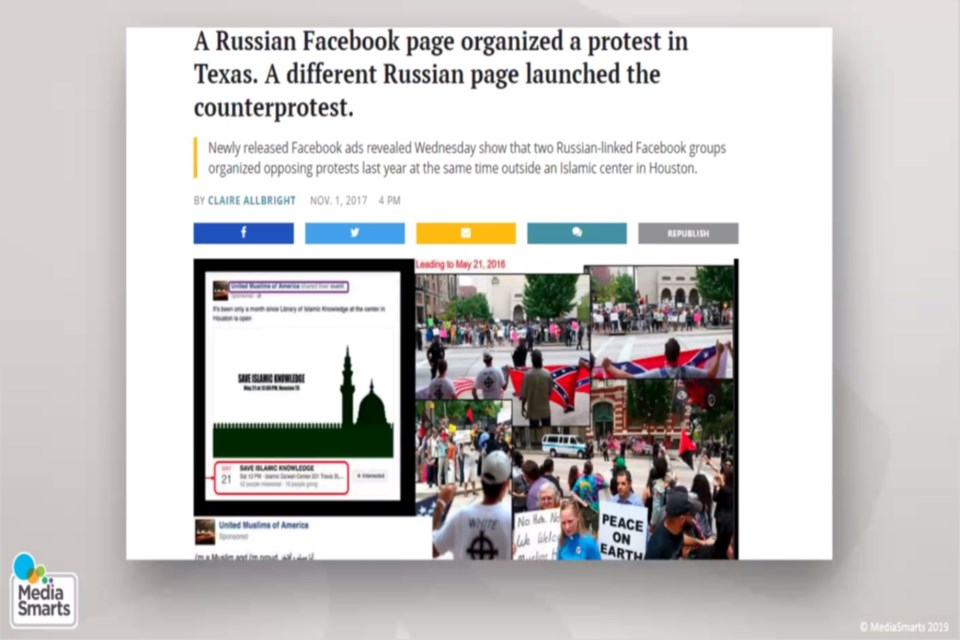

“A Russian troll factory had organized Facebook pages with rallies on both sides of an issue and the point was the troll factory didn't really care what the issue was,” she said. “They cared about sowing division and polarizing the conversation because that sowed the seeds of doubt and also makes it incredibly difficult for us to determine fact from fiction.”

The new campaign is sponsored by the Government of Canada, Bell Media, Corus Entertainment, APTN (Aboriginal People’s Television Network), and Family Television as well as Telus, Facebook, Tik Tok, Google, and the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada in the hopes Canadians learn how to think critically.

“Online misinformation hasn’t just made it easier to fool, it’s also made us more cynical and if we can’t tell what’s true, it feels safer sometimes to assume that everything is fake,” said Brisson-Biovin. “Critical thinking isn’t about doubting everything, it’s about learning how to find out what is true because only the truth can break the fake.”

Brisson-Boivin said websites like Snopes are excellent fact checkers, and anyone can submit an article to be checked. She did note Snopes leans to the U.S. media but if an article gains international attention the non-profit will pick it up to fact-check.

“Using fact checking tools – sometimes a single search can break the fake if a professional fact checker has already done that work for you,” she said. “Thanks to computers, it's easy to make fake pictures, and a lot of times people can share them without knowing that they're fake.”

Finding and verifying sources is an important tool as well, she said. Usually, people share the article so you can click on the original article and see who printed it. Reputable companies do not hide who wrote articles or ask for donations to keep their website from being “shut down by the government.”

“Another way you can see if someone has debunked a false or misleading news stories is to do a search for the topic of the story and add the words ‘fake’ or ‘hoax’ in your search,” said Brisson-Boivin.

Finally, Googling the headline should pull up other media outlets with related articles. If one “breaking news” article is only being shared by one media outlet without a byline – journalist name – or, no quotes from sources, and other ‘red flags’ then it is likely the article is fake, Brisson-Boivin said.

“You need to ask three questions – first does this source really exist? We saw … how easy it is to make fake photos online and it’s just as easy to make a fake website or social media profile,” she said. “Are they who they say they are? It’s also easy to impersonate people online and create imposter sites or social network accounts. And finally, are they reliable? Anyone can claim to be an expert online.”

The website has quizzes to test your fact-checking skills as well as materials for use in the classroom, office, or community.