He can't remember it all. But in fairness to 98 year old Glen Meyer, there was a lot to remember — and perhaps some things best forgotten — during the three years he fought for our freedom.

"It gets harder to remember. Sometimes, it's like a bad dream," said Meyer last week, just days before the 76th Remembrance Day that has come since his return from war.

Meyer was just 19 in 1943 when he left his parents' homestead farm near Caslan and went to fight. Meyer first went to Camrose to basic training, then to England for more training. His older brother Walter had left just a few months before. Walter was part of the Canadian Signal Corps that landed on the beaches of Normandy. Glen arrived on the Italian front in late1943, part of the Ontario Regiment of the Canadian First Armoured Brigade. He was a gunner operator inside a Sherman tank. He was in charge of the ammunition for the 75mm main gun and the machine gun. He also took care of the radio communications between the five men inside the tank and the dozens of other tank crews in the regiment.

Meyer's first combat action was at the Battle of Rome at Monte Cassino in early 1944.

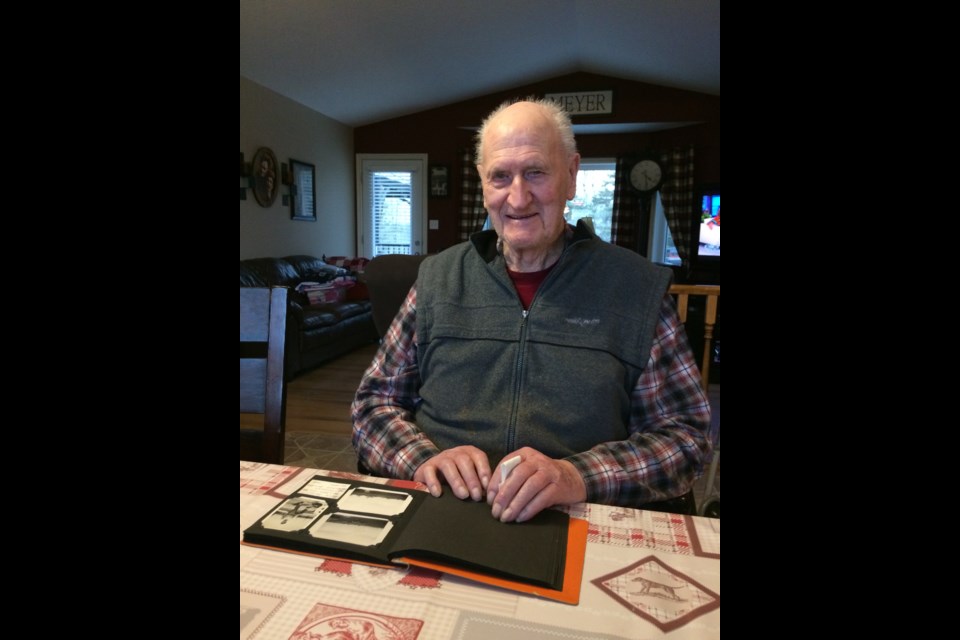

Last week, sitting at the kitchen table of his nephew's home near Hylo, Meyer recalled the long weeks of that battle. His hands are animated, showing how he would put a large shell into the breach of the gun, move his hand away quickly, tapping the gunner sitting below with the toe of his boot to indicate a live round was ready to fire. Two more times he makes the motions and then holds up three fingers.

Three.

That was how you knew you had a good team on the main gun. If you could get three shells in the air before the first one impacted.

Through the cold Italian winter, Meyer said his crew would camoflage their tank, create rough sleeping bunks from shell casings and fire at an enemy on the other side of a mountain range two kilometres away. Describing the cramped interior of the 35-tonne tank, his hands moving again, Meyer said he'd sleep sitting up in his chair beside the radio, shell casings all around him, with his arms crossed over for a pillow on top of the main gun's recoil guard. The crew rarely left the confines of the tank.

It was on one of the rare exits that Meyer was wounded by shrapnel from a German shell landing near his tank.

"I had to get out to pee," he said with a smile, explaining that when he heard incoming shells, he dove under his tank, but was struck in the back by shrapnel.

The injury resulted in a telegram being sent to his parents back in Caslan, informing them only that he had been injured in action.

Meyer had the shrapnel removed at a field hospital, but it wasn't until more than two months later that his parents received another telegram saying his injuries were not serious and he was still on duty.

He still has the telegrams, along with many other wartime collectibles including the leather-wrapped goggles he wore in the tank, canteens, carry bags, propaganda flyers and a coarse wool winter overcoat.

He has the memories as well. Moving from Italy after Rome was liberated, Meyer's tank and the rest of the Ontario Regiment were loaded onto boats for a trip that was supposed to drop them in the south of France. He remembers sitting on the deck, watching as the wind and waves pushed his e boat out of formation from the others. One of the boat's two engines had stopped working, forcing the vessel to be carried towards the shores of Spain — a neutral country, but one with ties to a fascist regime.

"They told us to just surrender and say nothing if the wind kept blowing us toward Spain and we were captured" Meyer said, remembering some pieces of his wartime with timeless clarity. "Then I remember the wind shifting, and we managed to get to France."

With France already liberated, Meyer said the tanks were loaded onto trains and sent to Holland where the last of the German forces on the Western Front were still fighting, trying to reach the Rhine River and destroying bridges as they retreated.

Arriving in France, Meyer said he remembers being asked by young children for chocolate. He remembers one boy in particular who asked the Canadian soldier if he was going to fight the Germans. Meyer said he was, and asked the the young boy if he liked the Germans, the boy said he didn't because a German stole his bicycle.

Retreating quickly and with much of their equipment destroyed, the Germans had grabbed what they could to leave France, many took bicycles.

When the tanks rolled into Holland, Meyer remembers seeing a pile of bicycles — with their tires stripped for the rubber — at the first bridge. The bikes had been left by the Germans as they met up with their retreating forces. In Arnhem, the location of the allied Operation Market Garden, an eventual turning point in the final months of the war, Meyer said the fighting was fierce. He recalls the sun being blotted from the sky by thousands of allied paratroopers and supply drops. He also remembers the bodies of paratroopers hanging lifeless in trees.

"It was a bad battle ... it was war," he said, explaining matter-of-factly that he saw some terrible things during his years on the front lines. He also experienced things so surreal, the memories sometimes seem like a dream.

Meyer's eyes brighten as he's asked by his nephew's wife to "tell the story about the pub in Holland."

The grin is wide.

"They have those stone streets, cobble-stones in Holland and they are quite slippery ... we were going pretty fast in the tank," he recalls, taking himself back almost 80 years. "Well it was a V-shaped corner we had to turn and there was a bar on the corner. We skidded and went right through the front of that place ... the guy was in there serving beer and we went in one side and out the other."

No one was hurt. In fact, Meyer said the barkeeper poured them beers when they stopped.

It was a few months later, in the spring of 1945, as the fighting diminished and the Germans continued to retreat and surrender, that Meyer learned the war in Europe was over. He was given a choice to remain in Holland as part of the liberating force, enlist to fight in the Pacific or return home.

Meyer was back in Caslan by the end of 1945, farming with his family. Walter was back home as well.

Meyer turns 99 in June of next year, 77 years after the Second World War ended in Europe. Walter Meyer passed away in 1976.

Rememberance Day

With the Lac La Biche Remembrance Day service being held outside this year, at the McGrane Branch Legion cenotaph, Meyer, who recently suffered a broken hip, isn't sure if he will be attending in person.

When asked about his service and his feelings about younger generations learning about the war and remembering the sacrifices from so long ago, Meyer remains matter-of fact.

"It is just something you had to do, and if I got asked, I'd do it again," he said.

The Lac La Biche Remembrance Day ceremonies will begin at 10:45 am on November 11.