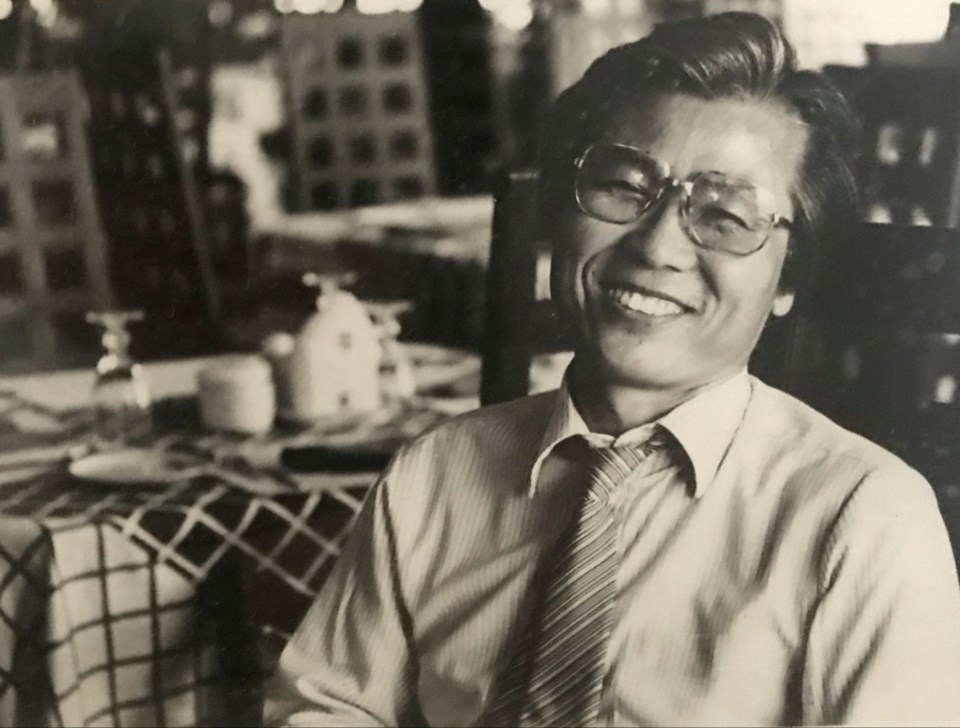

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Paul Shin, whose decadeslong career in journalism, including nearly 20 years with The Associated Press, placed him at the heart of South Korea’s most turbulent and transformative moments since the 1960s, has died. He was 84.

Shin had dealt with various health issues in recent years, including a worsening spinal condition. He died Tuesday morning at his home in Seongnam city, surrounded by his family, said his son, John Shin.

Shin, whose Korean name is Shin Ho-chul, landed his first reporting job in 1965 with the Seoul-based Korea Herald, and later worked for United Press International before joining the AP in 1986. After retiring from the AP as news editor in its Seoul bureau in 2003, Shin spent about 12 years mentoring and training English-service reporters at South Korea’s Yonhap news agency.

He covered many of the defining events that shaped postwar South Korea, from the era of harsh military dictatorships through the 1980s, to its dramatic economic ascent, the global spotlight of the 1988 Seoul Olympics and the turbulent cycles of confrontation and reconciliation with its war-divided rival, North Korea.

Shin was also part of a team of AP reporters led by Choe Sang-Hun, Charles J. Hanley, Martha Mendoza and Randy Herschaft who spent several years investigating the 1950 killing of Korean War refugees by U.S. troops in the South Korean village of No Gun Ri. The series won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting.

In writings and interviews, Shin recalled the early tough challenges of being one of the few international wire agency reporters in the country, navigating limited access to phones and wireless equipment and racing other reporters to secure telegram lines to file breaking news and claim scoops.

In 1973, Shin, then a UPI correspondent, didn’t have a phone at his new Seoul home. At dawn on one August day, he was awakened by a close friend and AFP reporter, who came to his house to share the news of opposition leader Kim Dae-jung returning home five days after he went missing at a Tokyo hotel. Kim, who was kidnapped by South Korean spy agents working for then authoritarian leader Park Chung-hee, later became president and won the 2000 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to promote democracy in South Korea and engage with North Korea.

In a 2006 book titled “Korea Witness,” a collection of essays and articles by Korea correspondents, Shin described the AFP reporter as “the tried-and-true friend” who searched for his house for almost three hours. With his help, “I was able to send out my first story about the release of Kim almost nine hours behind my competitors. I then rushed to Kim’s home for his news conference,” Shin wrote.

Later, Shin had a home phone but he said he knew both his home and office phones were tapped so he used public phones to communicate with sensitive sources and met a U.S. Embassy official in pre-planned arrangements to discuss political developments in South Korea. Shin said the U.S. Embassy official helped him to break the news about then-South Vietnamese ambassador to South Korea seeking asylum in the U.S., days after Saigon fell into the hands of North Vietnam in 1975.

During the back-to-back military-supported rules by Park and his strongman successor Chun Doo-hwan in the 1960-80s, Shin said authorities often intimidated and threatened South Korean reporters working for foreign media, but their counterparts at domestic media outlets suffered harsher treatments. Shin recalled local media voluntarily skipped sensitive stories and buried them on inside pages, saying such self-censorship "helped me get an unexpected scoop.”

At a meeting at the Korean border village of Panmunjom in 1980, North Korea abruptly issued a strong warning demanding South Korean ships sailing along the disputed western sea boundary receive North Korean approval. As the only foreign media reporter covering the meeting, Shin said he immediately phoned in the North Korean warning while South Korean media journalists did not, believing their stories would be dumped under their companies’ self-censorship.

“They were right. The story was never printed in any local newspapers,” Shin said, according to the book “Korea Witness.”

John Shin remembered his father as a “very warm and responsible person.”

“He frequently emphasized how important it is to communicate South Korea’s reality to the world and often expressed hope that younger generations of journalists would continue that role, especially now with South Korea being viewed through a more global lens,” John Shin said.

Paul Shin is survived by his wife, his son John, his daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren. The family is holding funeral services at Seoul’s St. Mary’s Hospital through Thursday morning.

Kim Tong-hyung And Hyung-jin Kim, The Associated Press