For some, Dr. Temple Grandin’s visit was a learning opportunity, for others, it was a chance to see through the eyes of someone with autism.

“It’s amazing that we have this chance, especially for me. I’m really looking forward to having more insight on how my son’s mind works. He’s non-verbal, so for us to talk to her (Grandin)… she might have some different strategies on how we might be able to help him,” expressed Tanya Stockwell, mother of a 20-year-old son with autism.

Tanya and her husband Blaine travelled to the area from Lac Ste. Anne County so they could learn more about the agricultural industry, and their own son.

Blaine said they heard of Grandin through her work in the ag industry. Since then, Tanya has read her books to get more insight into autism.

Their son is non-verbal, so getting the chance to speak with another person on the spectrum about autism is more than helpful.

“It’s nice to hear it from someone who can be verbal about it,” expressed Blaine.

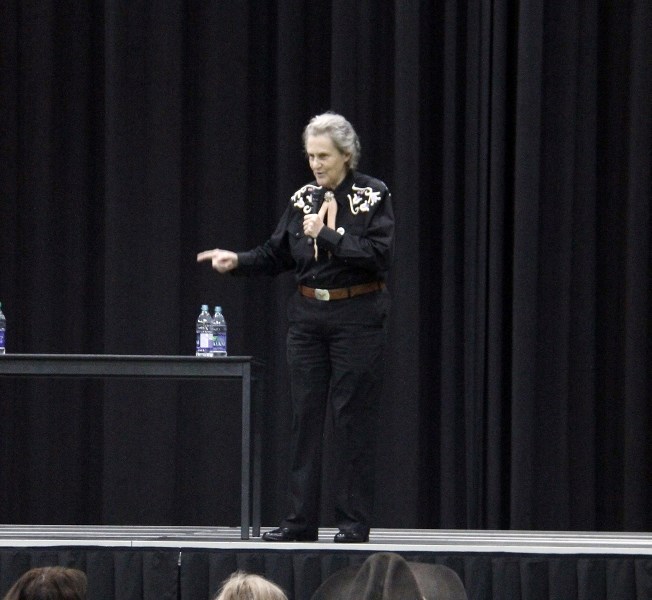

Grandin was in Bonnyville March 13 and 14. She spent both days speaking about topics she is well versed on; cattle farming and autism.

Her visit was an effort of the Rednecks with a Cause. They have been advocating for over two years to bring her to Bonnyville as a guest speaker.

Gary Mostert, president of the non-profit organization, said it was exciting to finally have Grandin in Bonnyville.

“It’s a huge honour to host Dr. Grandin, and I think that we have a crowd that appreciates her,” he expressed. “It’s almost overwhelming. You had all of this action and work for two-and-a-half years. Now that it’s here, we’re wondering how we top this.”

For the first day, Grandin shared her insight into the world of agriculture. She described how she came up with her cattle design system, triggers for cattle, and what not to do in the industry, among other topics.

The world-renowned speaker has been working on cattle handling since the early 70s, but her interest in the beef industry sparked at an early age.

“If you don’t get exposed to something, you won’t get interested in it. I was exposed to the beef industry at 15, which started the interest,” said Grandin.

Since then, she has done a “tremendous amount of work with packing plants.”

“The thing that I have done, and what probably improved animal welfare the most in packing plants, was a simple scoring system I developed,” Grandin explained. “You measure how many cows you stun on the first shot, how many fell down during handling, how many cattle mooed and bellowed during handling, how many you hit with the prod… the trick is figuring out the few things to measure that really matter.”

Grandin used her autism to her advantage.

As someone who thinks in pictures, she was able to understand the way cattle think.

“An animal doesn’t think in words. They’re going to think in memories stored as pictures, sound clips, and animals do a lot of communication through tone of voice,” she explained.

She also touched on the importance of stock handling and proper management.

“I thought I could fix everything with equipment. I can only fix half of the problems with equipment and the other half is management. Equipment is important, but I find, and this is true for autism too, is people want the thing more than the management. You have to have the management to go along with it.”

During her second day of presentations, Grandin discussed education and autism.

One thing she couldn’t stress enough, was early detection.

“If you have three-year-olds and two-year-olds who aren’t talking, you have to start working with them now. Don’t wait. You already have a diagnosis; it’s no-language. You have to start working with them now. Don’t let them veg-out on screens all day,” emphasized Grandin.

In 2013, the diagnostic criteria for autism was changed.

Grandin is concerned that everyone on the spectrum, regardless of his or her ability, is being put under the same label.

“To take Einstein and Edison, people who were socially awkward but brilliant, and put them on one end of the spectrum, and then have them under the same label as someone who can’t dress themselves. That doesn’t make much sense,” she expressed.

Sensory problems, sensory overload, the importance of encouraging and supporting your children in what they’re good at, and working with their abilities were also some topics she discussed.

“Sensory issues vary. Some have visual sensitivity, and others have sound sensitivity. In some cases, they can learn to tolerate that sound if they can control it, for example, a vacuum cleaner. Let the kid play with the vacuum cleaner where they turn it on and off. That can sometimes work,” described Grandin.

What parents need to keep in mind, is allowing their children to do things for themselves.

For example, Grandin believes in the importance of working outside of the home, even if they’re just odd jobs.

“I’m seeing a lot of smart kids who could be doing something like working in the oil field, and they never get a job and never learn how to work. They aren’t learning enough basic skills,” Grandin said.

For Mostert, bringing Grandin to the Lakeland was just the beginning.

He said, “We’re definitely going to be looking at more learning opportunities. We want to educate staff, parents, and service providers in the area, but we also want to create opportunities where the community gets to understand the child with autism, then the whole community can become more inclusive.”