Students in the Introductory Social Work class at Blue Quills First Nations College were treated to a unique and compelling story of human rights, and cultural issues on Nov 26.

Dilja Al-Rekabi, a social justice and human rights advocate, visited the college to speak about her experiences as a refugee. Al-Rekabi, originally from Iraq, came to Canada as a refugee from a camp on the border between Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

Al-Rekabi’s experiences reflect the cultural shock and social implications of being a refugee in Canada. Her talk touched on barriers between Canadians and the refugees and immigrants that come to the country.

Her story began during the Gulf War in 1991, when she and her family fled their home in Iraq and were forced into a refugee camp on the border between Iraq and Saudi Arabia for six years. She spoke of how difficult life was in the camp, and what the United Nations (UN) did to help immigrants leave.

She said the UN High Commission randomly selected families for assistance from delegations from participating countries. It was by chance that her family was selected for assistance from a Canadian delegation.

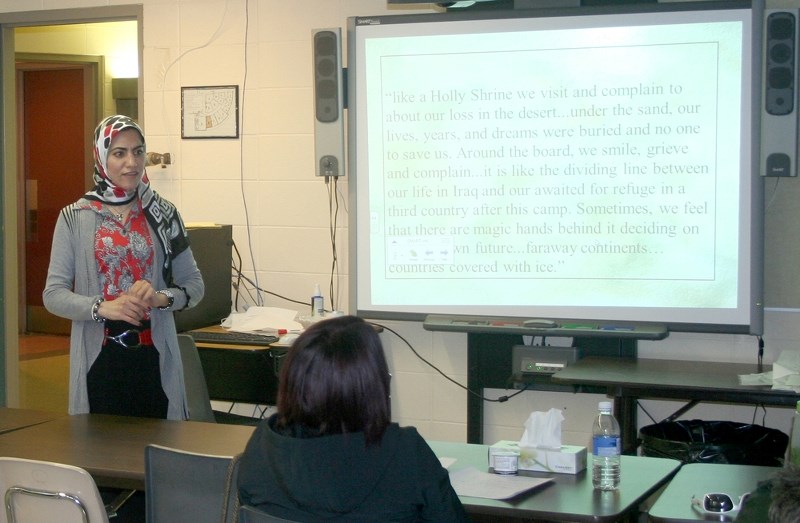

Al-Rekabi described the feelings of isolation and despair that characterized the camp, such as having to dress fully covered. She explained that their only means of communication with the outside world was a bulletin board where news of the families being selected for assistance from delegations with participating UN countries was posted.

“When confined to a place for six years, and it’s your only connection with the outside world, it’s important to you, it’s like a shrine,” said Al-Rekabi of the bulletin board.

During the presentation, a number of the staff and students from Blue Quills College noted a parallel between the discrimination, and misunderstanding that Al-Rekabi experienced as a refugee from a foreign country, to what is often described by First Nations people in Canada.

“I’m sure that First Nations people have had their share of the same stereotypes and racism,” said Al-Rekabi.

Even after being selected by the Canadian delegation, Al-Rekabi’s family faced stringent immigration laws such as the delegation not accepting families beyond a certain size, or families with disabled people, and the delegation wanting families to speak fluent English.

Al-Rekabi also touched on the compassion that she and her family experienced, with the delegate who interviewed her family accepting them, despite their limited grasp of English and other criteria they did not meet.

She said that she brought an Arabic-English dictionary, and an English dictionary, translating herself as best she could, telling the Canadian delegate of her family’s struggles at the camp where they lived.

After being accepted into Canada, Al-Rekabi explained that she faced difficulties.

“I felt like an uprooted tree. A refugee, in my mind, is like that. They are forced to survive or wither away.”

She added, “People would often say things like “aren’t you happy now that you can get an education,” not understanding that back in Iraq my sisters got full educations.”

Al-Rekabi and her family were immediately put into debt by the transition, and were expected to be fully self-sufficient within a year of arriving in the country. In addition to being in debt, Al-Rekabi became the head of the household, having learned English faster than her parents.

She faced other difficulties and barriers that included being conditioned by people educating her about the country, into prejudices against the First Nations people. She believed what she was told until she learned first-hand by talking to First Nations people herself, that many of the stereotypes people spoke of were false.

Al-Rekabi also offered students and staff some stories of compassion and caring. She describes the care a particular doctor took during an operation she had to have done, to ensure that her preferences as a Muslim woman were respected.

In closing, Al-Rekabi said, “People think refugees have a choice where they go, they do not. The UN High Commission does the process, and it is random. It wasn’t by choice that I came to Canada, but I am grateful that I’m here.”